The Victorian-era Anti-Slavery movement consisted of some of the most progressive and forward-thinking people of the age. But even they were, in a sense, trapped by the time they lived in, as was demonstrated when they found themselves baffled by the growing women's rights movement.

The scene was was the first General Anti-Slavery Convention, organised in 1840 by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Invitations to the event were sent out around the world in June 1839. However, this invitation did not specify the gender of the attendees, since the Society in question assumed that everyone would understand it was for men.

However, for the past two years in the United States, women had been pushing for equality in the campaign. These "Garrisonites" (named after a pro-feminist male campaigner) made it clear that they would attend and even ignored a second invitation sent in February 1840 which specified that only "gentlemen" were invited.

When the female delegates arrived, the organisers found themselves in a delicate situation. Their American colleagues were divided on the issue, and to make matters worse, the women were quick to make the most of any affront to their dignity.

In a debate on whether they should be allowed to attend, several British delegates pointed out that equality for women was against English custom, and that the Americans should respect that. The irony of this argument in an Anti-Slavery Convention was not lost on the visitors. Mr Bradburn remarked during the discussion:

"The invitation was extended to all abolitionists throughout the world; and no doubt it was earnestly desired, as well as designed, that they should all be represented here. [...] But we are now told, that it would be outraging the tastes, habits, customs, and prejudices of the English people, to allow women to sit in this Convention. [...] I depreciate the principle of this objection. In America it would exclude from our Conventions all persons of colour; for there, customs, habits, tastes, prejudices, would be outraged by their admission."

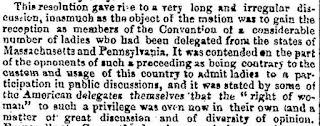

However, those delegates against admitting women made the case that it was not out of disrespect, but was also a practical measure made necessary by public opinion. Admitting women would open the Convention to ridicule.

The debate was wound up when delegates began to complain that such a discussion was preventing more pertinent talks. Samuel Prescod of Barbados insisted that the ladies told him they came here fully aware they would not be received, and that the debate had been improperly forced upon the convention. In turn, he was criticised for using the contents of a private conversation in a public debate.

In the end, the "Garrisonites" lost the vote heavily. The women took their places in the gallery as spectators, and so did Garrison himself, much to the amusement of the British delegates.

And that's how the first international anti-slavery convention started with a discussion about women's rights.

References

TEMPERLEY, H., (1972) “British Anti-Slavery 1833-1870”, Longman, p 85-92

“General Anti Slavery Convention” The Times (London, England), Saturday, Jun 13, 1840; pg. 7

“Proceedings of the General Anti-Slavery Convention”, British And Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, London, 1840, p 24-46

No comments:

Post a Comment