His book Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan contains an account of a walk through Matsue that fascinates with its details about the daily social events at temples, the passing pilgrims dressed in yellow straw overcoats and mushroom-shaped straw hats or the various cries of the late-night street pedlars. In these moments, when Lafacdio takes us through Matsue seeing Japan through his enraptured eyes, it’s easy to be transported back to mid-nineteenth century Japan.

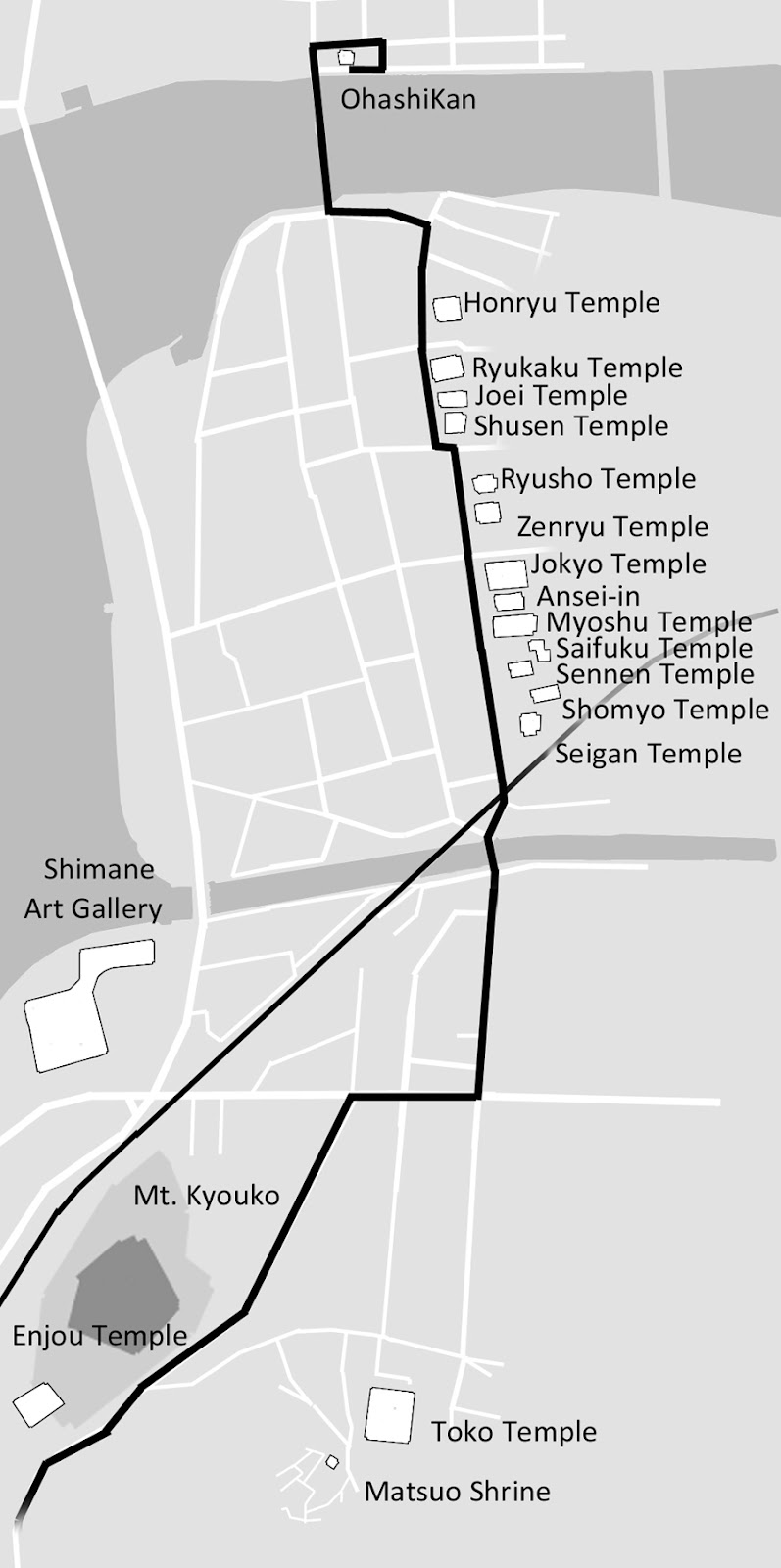

Let us take Lafcadio’s walk now, keeping his text close to hand, to see how things have changed.

He begins on the north shore of The Ohashi River, at the inn where he originally stayed named Tomitaya Inn. There’s still a hotel there called OhashiKan and, while there is an information board about Hearn by its entrance, it has precious few links to the old inn.

He goes into some length about the songs of birds, the emergence of schoolchildren and the comically loud horn on a new ship docked at the quay that used to sit on the river’s southern shore.

He guides us through a road that he calls “The Street of New Timber” which is the narrow road running parallel to the river on the other side of the inn. Hearn describes nets hung up on poles higher than the houses because, despite its name, the street housed fisherman. These days, the only poles here hold up Japan’s complicated network of air-borne wires and cables. These do have an air of Lafcadio’s “prodigious cobwebs against the sky,” but I suspect the atmosphere has changed considerably over the years.

Then he crosses the Ohashi bridge, admiring the mountain Dai-san in the distance to the east as he does (this part, at least, has not changed since Lafcadio’s time) and he describes a very small Jizo temple at the end of the bridge which has now gone.

He writes at length about this bridge. During his stay it was rebuilt, changing from a bridge that "curved over the flood, supported on multitudinous feet like a centipede of the innocuous kind" to an iron construction whose girders formed triangles along the bridge.

Lafcadio describes a well-known fable relating to the bridge. It states that the construction was beset by difficulties and the pillars of the bridge would repeatedly be swept away no matter how many stones they sunk into the river bed. Finally, the daimyo who was overseeing the construction of the new city, decided the only course of action was to have a human sacrifice: a hitobashira, or human pillar, who would be buried alive in the structure of the bridge.

The choice was made at random: the first person to cross the bridge wearing hakama (a kind of trouser) without a machi (a rigid board that covers the knots of the hakama at the back) would be the victim. One man, named Gensuke, crossed in this manner of attire and was swiftly made a sacrifice. According to Hearn, this lead to the bridge standing firm for another three hundred years. The middle pillar of the bridge was called Gensuke’s Pillar, and a flickering red light was sometimes seen over the bridge. Hearn recounts this legend in a newspaper article where he describes in some detail the opening ceremony of the 15th Ohashi Bridge.

Hearn explains how the widespread belief in the Gensuke legend persisted to his present day: how the building of the new bridge caused rumours to circulate that a similar fate could await some unsuspecting citizen: not the first to cross it, but the thousandth. Hearn writes how the question “Has the victim been caught yet?” was commonplace among visitors as they arrived. Despite the superstition, people still flocked to the opening ceremony. Hearn guesses the crowds numbered twenty thousand and said the river was so full of boats of spectators that “one could easily have passed the Ohashi by stepping from one to the other”. When the ceremony was over and the bridge became open to all, there was a huge roar and the citizens of the town swarmed across it, all suspicions apparently forgotten.

Then Hearn guides us towards Tenjinmachi which, he reminds us, is also called the Street of the Rich Merchants. As we approach the end of the bridge looking south, it is directly ahead of us. The dark blue hangings with “white wondrous ideographs” that adorned the shops on both sides have gone. As has much of the energy of the area. Hearn said it contained “the richest and busiest life of the city” where you could find many curious temples as well as “the theatres, and the place where wrestling-matches are held, and most of the resorts of pleasure.” This all changed with the opening of the train station in 1911 which meant goods would no longer arrive in Matsue via Lake Shinji, so instead the area around the station became more prosperous and Tenjinmachi slid into decline. Now this area is best known for its aging population.

We won’t go this way since Lafcadio doesn’t go into any real detail about Tenjinmachi in his book. Instead, we’re going to take a left once we step off the bridge, past a small memorial to an engineer who died in the construction of the current bridge. There is also a long, flat roughly hewn stone here with an information board beside it. This is a musical stone of Oba which, according to the legend recorded by Lafcadio, can only be transported a certain distance. Apparently, one of the Matsudaira feudal lords (Hearn doesn’t specify which one) wanted one in the castle grounds but as they approached Ohashi Bridge the stone became so heavy that not even a thousand men could move it so they left it by the bridge, where it remains to this day.

Walk past this stone and follow the road as it bends south. Now we’re heading into the neighbourhood called Wadamicho (多見町) towards Teramachi (寺町 lit, “Temple Town”) which is a neighbourhood where temples cluster together. When the city was created in 1611, this area also served a military purpose in that the walls of the various temples would offer at least some defence against any attacking forces coming from the south-east. Hearn describes this area as “masses of Buddhist architecture mixed with shreds of gardens and miniature homesteads, a huge labyrinth of mouldering courts and fragments of streets”. When Hearn wrote about these temples, he was struck by how children use the forecourts as playgrounds and how many of them have wrestling rings in the grounds where people can wrestle or watch for free during the summer months.

Things are a little different now, of course. While a district of temples with a history dating back to the 1600s sounds a chance to stroll through avenues of ancient architecture redolent of a vanished age, then one needs to be reminded that these temples are all still in use. The religious sites in Teramachi are pristine and, often, quite similar with black tiled buildings, a courtyard, and little else to distinguish it from its near neighbours. Additionally, Teramachi is no longer on the outskirts but is in the centre of the city, barely ten minutes’ walk from the station, such that any sense of quiet contemplation can't really be sustained while walking from one temple to the next. But we’ll head this way and I’ll try to give a little history of the place with whatever stories I happened to have heard.

The first temple we come to is on our left and is called Honryu Temple (本竜寺 Honryuji) this temple is more notable for what it lacks than what it has. In 2018, its 175 year old gate had to be demolished because it had become so weak that it would be a hazard in an earthquake. Now, in it’s place, is a clean white wall with pillars either side of the entrance where the gate once stood.

As we continue we soon come to, on our left, Ryukaku Temple (龍覚寺 Ryukakuji) whose gate is still intact – a gleaming white edifice of smooth concrete (I assume). This temple houses a Buddha statue that was found floating in Lake Shinji by a sailor. Next is Joei Temple (常栄寺 Joeiji), which is so close that it shares the same external wall as Ryukaku Temple but whose history eludes me.

Carry on following the white wall until we come to a staggered crossroads, with the road heading south a little to our left. At this junction is Shusen Temple (宗泉寺 Shusenji). I mentioned before how temples would hold wrestling matches, and this temple hosted a fight between two martial artists. One was a monk, Takeda Matsugai, who was famous for his feats of strength. People would ask him to punch wooden pillars in their house, leaving behind the imprint of his fist, as a mark of friendship. He stayed at this temple in 1850 and during that time and he fought against Ogura Rokuzo, later to become the 11th master of the Jinshinryu school of Judo. Matsugai won by throwing his opponent into some tea plants.

We’ll continue south, now walking through Teramachi itself, and we’ll soon arrive at Ryusho Temple (龍昌寺 Ryushoji) with an information board relating to Lafcadio Hearn. It tells us that he would often walk around the graveyard here and once happened upon a Jizo statue. Struck by its beauty, he asked if it were the work of a master craftsman which, indeed, it turned out to be. This confirmed Hearn’s reputation as a connoisseur of art.

The next temple along is Zenryu Temple (全龍寺 Zenryuji). It’s records were lost in a fire, but it does have one notable feature from more modern times. In the cemetery here is the grave of Yamauchi Kakugawa, a poet who was born in the adjacent neighbourhood Tenjinmachi in 1817. Tenjinmachi would have been at its height of its powers as a hub of trade and entertainment at this time. He became an antiques dealer which kindled his interest in the tea ceremony and, from that, haiku poetry. He corresponded with a poet in Kyoto and became more determined to follow poetry as a vocation.

One day, he performed a tea ceremony for his wife as a symbolic way of saying goodbye and, three days later, left Matsue during a snowstorm. He studied in Kyoto and then Edo, before travelling north. Finally, aged 41, he returned to Matsue where he built a hermitage and taught about poetry and the tea ceremony until his death in 1894. His gravestone here carries the inscription 何ひとつ見えねど露の明りかな “I can see nothing but the light of the dew”.

On reaching the crossroads and we can already see the next temple sitting on the junction, just ahead and to our left. This is Jokyo Temple (常教寺 Jokyoji) a temple of the Nichiren Buddhist sect with a statue of Nichiren beside the gate as you enter.

The cemetery here houses the grave of Kobayashi Jodei, a local woodworker who died in 1813. He worked for the 7th lord of Matsue, Matsudaira Harusato, and was famous in his day for his skill. He was also an alcoholic, apparently always drunk, and even invented a wooden sake cup that wouldn’t leak. One story about him details how a young carpenter, indignant that such an old soak should enjoy the patronage of the feudal lord, challenged him to a wood-carving competition...

Kobayashi agreed on the grounds that they both carve mice. The next day, in front of several people, they presented their works. The mouse of the younger carpenter was exquisite. The fur, the tail, the ears, everything was done to perfection. The mouse carved by Kobayashi, well, it looked like a mouse, but was a little sloppy. The young challenger was announced as the winner when Kobayashi raised an objection.

“Surely the best judge of which is more realistic should be a cat,” he insisted and his opponent, thinking it would make no difference, happily agreed.

So a cat was brought in and the two wooden mice put in front of him. The cat immediately pounced on Kobayashi’s mouse and the contest was definitively decided in his favour, leaving the challenger ruing his insolence and amazed at the talent that could fool a cat.

Later that evening, Kobayashi was out drinking when the bartender asked him why he thought the cat preferred his.

“Well,” said Kobayashi, “his mouse was better than mine but, the thing is, he’d carved his from wood, while mine was made from dried fish.”

Following on from this are a number of temples about which I can find little. The first two have impressive gates while the ones further south are tucked away behind shops and houses, accessible down paved alleyways.

Finally we arrive at a junction where the railway line passes overhead. Looking to our left we can see the green roof of another temple gate. This one, the southernmost in Teramachi, is Seigan Temple (誓願寺 Seiganji) and was once a favourite of the Matsudaira family, famous for its opulence.

After this, Lafcadio Hearn passes over the Tenjin Bridge which as far as we’re concerned is under the railway and down the road as it veers right. In Lafcadio’s day this passed over the Shinedote River, but this is now called Tenjin River, and this road lead into what was then a more run down densely populated area with “many a tenantless and mouldering feudal homestead.” These days it’s a residential area whose roads are shaped by the railway line running through it, but it isn’t particularly decrepit or abandoned.

He heads south-west to a soba Noodle shop named Kuribara where he can watch the sunset over the lake but gives scant details that we can follow. However, further south of this neighbourhood there is another location that he wrote about: Toko Temple. He visited here in unfortunate circumstances – for the funeral of one of his students. Hearn described the interior of the main hall, with its candelabras with brass dragons and vessels shaped like deer, tortoise, and stork, but most profoundly he recounted the bell and the sound it made on this onerous day. “Peal on peal of its rich bronze thunder shakes over the lake, surges over the roofs of the town, and breaks in deep sobs of sound against the green circle of the hills.”

After his visit to the soba shop, Lafcadio briefly describes his journey as he retraces his steps. On his way back over the Tenjin Bridge in twilight he passes a woman praying for her dead child, dropping strips of paper into the water below, each one with the image of a Jizo Buddha and perhaps an inscription upon it. Once back at the inn, Lafcadio describes the final sounds of the day and the “soft Buddhist thunder” of the bell at Toko Temple in the distance, a few streets from the Soba shop he’d visited earlier.

This passage, which takes up Chapter seven of Glimpses of an Unfamilar Japan, is endearing in its lapses into rhapsodic utterances over minor details. He diligently transcribes the calls of the street vendors, describes students marching past and lists any number of minutiae so banal that most people wouldn’t even think to write about them but Lafcadio captures them in style so we can revisit his Matsue, sharing in his joy at every new discovery.

Hearn’s life in Matsue was by no means perfect. The winter, in particular, disagreed with him. Unable to face a second winter Hearn left Matsue in the summer of 1891 for Kumamoto in the south and, initially, the change was not a happy one. He found the locals too reserved and even the local superstitions which had so delighted him before now seemed hopelessly backward. But the climate suited him and, in time, he came to appreciate his new home. In 1894 he moved to Kobe to work for a newspaper there. In 1896 he became a Japanese citizen and took the name Koizumi Yakumo. A year after this he took a teaching post in Tokyo and lived in that city for the rest of his life.

Lafcadio Hearn passed away in 1904 of a heart attack. The renown he’d built up during his lifetime in the West was slowly undone by Japan’s military expansionism which didn’t sit well with Hearn’s image of a quaint spiritual Japan. Meanwhile, In Japan he initially remained a largely unknown figure, even in the town he most adored. The French author Andre Bellessort visited Matsue in 1919, keen to see Hearn’s home for himself, but he had to go to the local government offices before he found someone who knew where it was.

This changed in the 1920s when Hearn’s work was translated into Japanese for the first time. The Japanese ruling elite were keen to spread the word about this author as an example of a Westerner who really understood Japan, and whose emphasis on old traditions and legends was an image of Japan they wished to maintain. Lafcadio would have been appalled at his work being used to support a regime that he’d despaired at during his lifetime. In his later years he became more cantankerous, disappointed at the country Japan had become. “Carpets – pianos – windows – curtains – brass bands – churches! How I hate them!!” he wrote. A friend of his, Yone Noguchi, recalled Hearn had once said “What is there, after all, to love in Japan except what is passing away?”

These days his reputation sits uncomfortably on two stools. He could be considered as a chronicler of places and stories that most journalists wouldn’t even consider and, as such, he was remarkably ahead of his time. On the other hand, he was a traditionalist, overburdened by nostalgia and spending most of his later life basing his writings on memories or old note books rather than the rapidly-changing world outside. But for all his faults he remains an important and engaging writer from the late Victorian-era who captured something of a now disappeared Japan.

Lafcadio Hearn’s last visit to Matsue was in 1897, just before he moved to Tokyo. He wrote about it for the periodical Atlantic Monthly where he explained his trepidation

“I felt curious in advance as to the nature of the impressions I was going to receive on revisiting, after years of absence, a place known only in the time when I imagined that all Japan was like Izumo.”

He visited his old house with its much-loved garden and the school where he’d taught and, most importantly, an old friend Sentaro Nishida who was suffering with the later stages of tuberculosis.

Hearn’s final departure from Matsue was by steamer, departing from a quayside near Ohashi Bridge where he had first arrived. He was accompanied by Nishida despite the stifling summer weather. This would be the last time that the two friends met and Hearn expressed a pang of regret at his friend’s hospitality in a letter he wrote shortly after.

“I felt unhappy at the Ohashi, because you waited so long, and I had no power to coax you to go home. I can still see you sitting there so kindly and patiently – in the great heat of that afternoon. Write soon – if only a line in Japanese – to tell us how you are.”

And he ends the letter with a brief sentence below his signature that reads,

“I still see you sitting at the wharf to watch us go. I think I shall always see you there.”