Furthermore, this experiment has never been written up in any real detail, neither for peer-reviewed publication nor internal memo for the CIA. Instead, details about it are scattered across several different sources. I thought it’d be worth putting together as much information as possible to give a little more context to this remarkable event.

What was the purpose of the experiment?

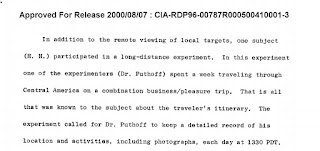

This was a long-range remote viewing experiment, with Hal Puthoff acting as the beacon. He went on a business/pleasure trip to Costa Rica in April 1974. The trip lasted ten days and “a week of remote target viewing” was carried out, with each session taking place at 1330 PDT (1430 CST, the time zone in Costa Rica) at which point Hal would take notes of his current location, including taking photographs.

The experiment was first mentioned in Progress Report No. 2, which is dated 24th April 1974. This is actually a week or so after the sessions were complete, but it’s clear that the report was written some time before publication.

How many sessions was the experiment designed to last?

Seven sessions, taking place in consecutive daily sessions.

Who were the remote viewers?

There were two remote viewers, Pat Price and Hella Hammid, with Russell Targ filling in for an absent remote viewer on one day.

In the book Mind Reach, Targ and Puthoff state that one was in Los Angeles and the other in Menlo Park (ie, at SRI). They did not specify which one was which, but it is more likely that Hella Hammid worked from Los Angeles while Pat Price was at SRI.

However, according to Targ and Puthoff’s 1974 paper “Remote Viewing of Natural Targets,” Hella Hammid was the only remote viewer on this project. Pat Price, despite being mentioned in other parts of the same paper, has been removed entirely from this version of events.

Were the remote viewers blind to the target?

Not completely. In Progress Report No. 3 we learn that the two remote viewers were told that the beacon was Hal Puthoff and he was travelling in Costa Rica.

Which remote viewer did not arrive for the session?

In Targ and Katra’s book Miracles of Mind, it is Pat Price who is absent. However, it is troubling how much Targ’s 1998 version of events differs from the classified documentation. According to this book, the experiment took place in April 1973 (it should be April 1974. In fact, Pat Price hadn’t even joined the team in April 1973) and each session happened at 9.00am (not half past one in the afternoon).

And, of course, in the 1974 paper which removed Pat Price from proceedings, Hella Hammid is named as the psychic who did not turn up.

However, it appears that neither attended. The classified report “Perceptual Augmentation Techniques: Part Two” states that the experimenter “acted as a subject in one experiment on a day in which S4 [ie, Hella Hammid] was not available and the other subject arrived late.” Bearing in mind the quote from Mind Reach telling us that Hella Hammid was based in Los Angeles, if we consider the use of the phrase “not available” it seems to me that Targ already knew Hammid couldn’t submit a session for that day and so when Pat Price did not arrive in time on Friday, Russell Targ submitted his own remote viewing session rather than have one day with no remote viewing data at all.

Was the experimenter blind to the target?

Varous accounts talk about keeping Hal Puthoff's itinerary a secret from the subjects, but there's no mention of doing the same for the experimenter Russell Targ. In Progress Report No.2, when the experiment is first described, it says that the experimenter would also attempt to blind match the session transcripts to the beacon’s target pictures after Puthoff had returned. However, no attempt to complete this part of the protocol was made. Does this mean that Russell Targ had become non-blind to the targets before the judging process could take place? How long was the gap between Puthoff’s return and the photographs being developed? Targ and Katra’s book states “several weeks” but, given the many inaccuracies in that version of events, one has to wonder if this is another mistake.

What happened on the day that Russell Targ did his remote viewing session?

Friday 12 April 1974 was Good Friday that year.

In a recent presentation about his work at SRI, Hal Puthoff explained how he “had a chance to trick” the remote viewers by jumping on a plane and flying to a nearby Colombian island in time for the session. An online airline timetable archive has a LACSA timetable for 1973 which, if we assume that airline timetables don’t change drastically from year to year, confirms that there was a service from Costa Rica to San Andres, Colombia on Fridays (another LACSA timetable dated 1979 has the Friday service still listed). Hal Puthoff would’ve taken the flight from San Jose Airport in Costa Rica to San Andres Airport, but would’ve had to have taken the next flight back or remain there until Monday, meaning he was only on the island for about an hour.

Despite Targ and Puthoff supplying contradictory reports in different accounts, we can be pretty sure that it was Pat Price who did not arrive on time at SRI that day. During these early days in the project, they were still assuming that remote viewing happened in real-time: moving the remote viewer’s perception through the past or the future had not yet been attempted. As such, Pat Price’s absence at that specific time was a problem. Russell Targ has since described his decision to submit a session himself as being done in a spirit of “the show must go on.” Russell Targ’s sketch is dated 4/12/73 (getting the year wrong) and it lasted from 1:25-1:30.

What were the results of the experiment?

Twelve remote viewing sessions were completed: Six by Pat Price, five by Hella Hammid and one by Russell Targ. On his return, Hal Puthoff correctly matched five of these twelve sessions to his seven daily reports, two for Price, two for Hammid and Targ’s session, at odds of 50 to 1 (we shall assume that the notes were given to him with the dates removed).

The content of the sessions by Price and Hammid is largely unknown, except for brief mentions of descriptions of Puthoff relaxing by a pool, in his hotel room or in a jungle environment near a flat-topped mountain (this last session has been credited to both Price and Hammid in different accounts).

The photo that usually accompanies Russell Targ’s sketch is not the same photo that Puthoff took. His two photos were taken from the ground. The aerial photo doesn’t appear until 1977, in the book Mind Reach.

The response to this result was positive, but guarded. An anonymous review of the SRI work to date written in 1975 points out that the full data had still not been submitted, and so any definitive conclusion could not be drawn.

References:

Progress Report No. 2: Perceptual Augmentation Techniques, CIA-RDP96-00791R000200040004-9

Review of Perceptual Augmentation Techniques, CIA-RDP96-00787R000200150004-2

Perceptual Augmentation Techniques: Part Two – Research Report, CIA-RDP96-00791R000300030004-9

Karen Wehrstein (2018). ‘Russell Targ’. Psi Encyclopedia.

Targ, R., Katra, J. (1999) Miracles of Mind: Exploring Nonlocal Consciousness and Spiritual Healing,” New World Library, Ca, USA.

Targ, R., Puthoff, H. (1974). Remote Viewing of Natural Targets. Conference on Quantum Physics and Parapsychology, Geneva, Switzerland, August 26-27, 1974.

Targ, R., Puthoff, H., (1977) “Mind Reach: Scientists Look at Psychic Ability,” Delacorte Press

Dr. Hal Puthoff, PhD, on CIA History of Top Secret Remote Viewing